An Insecure Pillar in Cybersecurity.

The story goes that Caesar, to exchange secret messages with his generals in the field, used to shave his messengers bald and write the message on their scalps. He would then wait a few months for their hair to grow back and send them off to their destinations. Only his trusted generals would know of this method to exchange messages, thus delivering his orders securely (albeit a few months late).

This impractical, and rather silly, example describes what cryptology is all about. Cryptology is the science of securing communication. The term is taken from the Greek kryptós ("hidden, secret") and lógos ("word"). In essence, it is about "hiding words". It is only one pillar in the science of Cybersecurity, but it is a significant one. At the base of this pillar are the subdivisions of cryptology: Cryptography and Cryptanalysis. The two can almost be seen as complementary. Where cryptography is the practice of transforming communications into a form that is unreadable to eavesdroppers, cryptanalysis is the practice of trying to unravel those transformed messages by an unintended recipient.

So, enter the Pantheon, this temple of Cybersecurity if you will, and let me guide you to where the cracks in the Corinthian columns begin to show.

There are many different algorithms designed to keep messages secure. I'm going to tell you a bit about some of those systems so that the foundation of these algorithms becomes clear.

If you've read anything about cryptography, chances are you've come across a concept called the "Caesar cipher". This is another example of a method used to secure messages. It is also attributed to Caesar, although this one doesn't involve a messenger's locks (pun intended) to keep the message safe. Instead, this cipher introduces an important concept that a significant portion of cryptographic algorithms are based on: Modular Arithmetic.

I know, I know. It sounds scary, right? What if I told you, it's so simple that you use it every day? See, your clock is based on modular arithmetic as well. When you're trying to figure out how much sleep you're going to get if you have to wake up at 06:00, as you're finishing up that deadline at 23:00, you know not to count past 24:00. The result is always going to be less than 24:00. You're essentially calculating modulo 24. This is modular arithmetic, and it is used extensively in cryptography. Even in its simplicity, though, modular arithmetic holds many secrets that aren't immediately evident. Many cryptographic algorithms rely on these secrets.

Caesar's cipher is a symmetric cipher. This means that both parties use the same key. Let's say the key is 3. The sender would shift every letter of his message by 3. This is called encryption. The receiver needs to know the key, and would then shift back every letter by 3, obtaining the original message. This is called decryption. Compare this to the bald messenger method. Encryption is letting the messenger's hair grow over the message, decryption is shaving the messenger bald.

Now, is the Caesar cipher very secure? Well, not really. Anyone can easily try all the different keys, of which there are 26 in total, and find the correct one to unravel the message. This is called a Brute Force Attack. While the cipher is not very secure, it does adhere to an important principle that Caesar's bald messengers do not adhere to. Kerckhoffs principle states:

"A cipher should not require secrecy, and it should not be a problem if it falls into enemy hands."

In other words, the principle states that only the key should remain secret. The method may be made public, but without the key, the message should remain secure.

If Caesar's formerly bald messenger gets intercepted by the enemy and the interceptor is aware of the method used by Caesar, the poor messenger will be shaved bald again in no time, revealing the message on his scalp. With Caesar's cipher, however, even if the interceptor knows the method of encryption, he would still have to try 26 different keys to uncover the message.

Caesar's cipher is one of the simplest ciphers in existence, but its simplicity nicely demonstrates aspects of modular arithmetic. Other common symmetric cryptosystems are DES, 3DES, and AES. They essentially do the same thing as Caesar's cipher, albeit way more complex and harder to brute force. If you want to read more about these systems, I highly recommend reading the AES Comic.

Let's introduce another important concept. Asymmetric cryptography (or public-key cryptography). The difference is that instead of the two parties having the same key, they have their own public and secret keys.

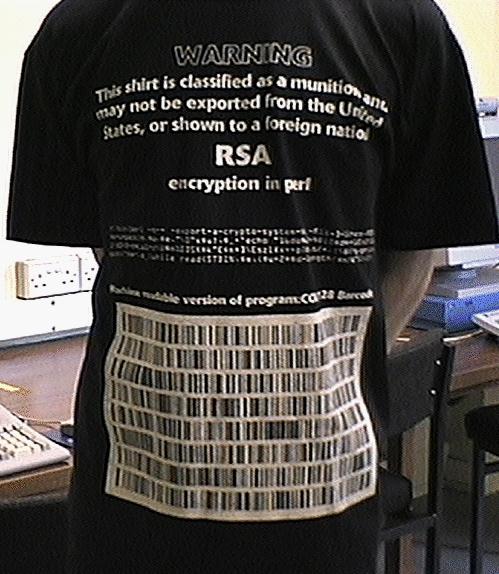

Before we dive into RSA, here's a cool tidbit about it for you. When RSA was invented by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman, it was illegal for them to export the algorithm or even its description, as part of munitions control in the US. RSA was considered so powerful that it was to be kept a military secret. As a freedom of speech protest, they wore T-shirts with the algorithm printed on them to conventions and talks.

RSA is the most popular public-key cryptosystem. It's a super cool system that perfectly illustrates what a lot of modern cryptography is based on. We're going to get a bit technical here but bear with me.

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that any positive number can be represented in exactly one way as a product of one or more primes. For example, the number 77 can be represented by multiplication of 7 (a prime) and 11 (a prime). There is no other way to represent 77 in primes apart from changing the order of the primes. Keep this in mind while I explain RSA.

Before a message can be sent, we need to do some setup. Say, Bob wants to send a message to Alice and there is some eavesdropper called Eve. Alice, as the receiver, chooses two large prime numbers. She multiplies these two numbers to get the result m, the modulus. We're going to keep it simple and small in our example. Alice chooses 7 and 11 as prime numbers, resulting in the modulus 77. She publishes the modulus 77 and some chosen encryption exponent e. The combination of the modulus 77 and the encryption exponent e is called her public key. With Alice's public key Bob can encrypt the message he wants to send. In this case, the message is a number x. Encryption in RSA is done by taking xe mod m. This results in ciphertext y and sends this to Alice. Now, Alice can do some magic with the prime factors 7 and 11, which results in a piece of information called d (for decryption). This is Alice's secret key. All Alice has to do now is take yd, which will result in Bob's original message x.

Phew, that was a lot, but the hard part is over! Now, notice that only Alice knows prime factors 7 and 11. This means that only Alice can do that magic trick to get information d. But if you're sharp you would disagree with mere here. You'd say: "Since 77 is published and everyone has access to it, Eve can easily figure out that 77 = 7*11 and do the magic trick as well to obtain d, with which she can get the original message x". I would agree with you here. Then I would tell you: "What are the primes of the number 30142741". Chances are you won't be able to tell me the answer. I can very easily tell you the answer though since all I did was take two prime numbers and multiply them to get 30142741. And if I told you those two numbers, you could just as easily verify that the product is 30142741. So indeed, RSA relies on Eve (or you) not being able to find those two primes. In this case, the primes are 6037 and 4993. See how difficult prime factorization is, but how easy it is to verify the correct primes?

That's it! We are finally at the base of the pillar. Do you see the cracks? Probably not. Let me clarify.

So, the transformations we apply to the message (encryption) need to be invertible for the receiver to be able to decrypt it. The receiver can invert the message because she is in possession of some extra information. Meanwhile, any interceptor, not in possession of that information, will not be able to decrypt the message. In RSA, for example, the interceptor would need to find the two prime factors of the modulus. Finding the two prime factors of a small number like 77 is, of course, easy, but prime factorization becomes much harder when a large number is chosen. Verifying that the two primes are factors of the modulus is always relatively easy since you just do multiplications.

If prime factorization was easy or if there was an algorithm that can solve the problem relatively fast, then RSA would become obsolete. It relies on prime factorization being hard to solve, but easy to verify. We can make a distinction between two sets of problems. There are problems for which we know a way to find the answer quickly, for example, multiplication or squaring. This set is called "class P". The other class, "NP" is a set of problems for which there are no known ways to find an answer quickly, but when you have some information, the answer is easily verifiable. Prime factorization belongs to this class.

But what if there is a way to solve a prime factorization problem easily? This would imply that prime factorization belongs to the P class. In fact, maybe we could prove that all NP problems are actually P problems. The conclusion would be that P = NP.

This conclusion would have disastrous consequences for cryptography. As we've seen, RSA relies on prime factorization being difficult to solve. But RSA is only one of many algorithms that rely on NP problems and prime factorization is only one example of an NP problem. Other symmetric and asymmetric ciphers used for your financial transactions, your e-mail communication, etc. would be rendered obsolete.

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies would suffer severe consequences as well since Bitcoin relies on cryptographic hashing, specifically, the SHA-256 hashing algorithm. For a new block to be accepted in the blockchain, this new block needs to contain a proof-of-work. In short, the proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but generating the correct number is extremely hard.

Proof of P = NP could on the other hand have positive consequences for other fields. Many mathematical problems remain hard to solve. Just imagine the effects it could have on mathematics!

Proof of P ≠ NP would mean that our cryptographic algorithms are secure and that the title of this article is just clickbait. But at least I offered you the chance to win a million dollars! That's the reward the Clay Mathematics Institute will award to the first person to solve the "P vs NP" problem.

So, give it a shot! Maybe you could be the one to break modern cryptography and send us back to using bald messengers for our daily communication.

Let me know your thoughts on the matter.

If you’ve got any questions, reach out to me at info@redpointwriting.com!

Also seen on hackernoon